Dynamic analysis is essential whenever structural response is dominated by inertia, vibration, resonance, shock, or time-varying loads. It answers a different question than static checks: How will the product behave in real operating conditions?

Dynamic analysis helps predict resonance-driven amplification and vibration-induced failure modes before testing or field use.

Static strength alone is not enough

A product can pass static strength checks and still experience severe problems once exposed to real operating conditions. When loads change with time, inertia and resonance can dominate the response—causing stresses, deflections, and noise far beyond what static predictions suggest.

Static analysis asks: Can it carry the load?

Dynamic analysis asks: How does it behave when motion and time-varying forces are present?

Why dynamic failures are so costly

Dynamic issues often show up late—during system integration, qualification testing, or after launch. At that stage, fixes are disruptive and expensive.

Common failure outcomes

- Unexpected vibration → noise, loosened fasteners, cracked parts

- Resonance amplification → stresses far above static estimates

- Premature fatigue → lifecycle failures from cyclic excitation

- Performance drift → misalignment, loss of precision, degraded output

Business impact

- Warranty cost and returns

- Redesign loops and schedule slips

- Additional test cycles and re-qualification

- Reputation risk and loss of customer trust

What dynamic analysis provides decision makers

- Early identification of resonance risk (mode shapes + natural frequencies)

- Prediction of vibration-driven amplification (harmonic / random response)

- Improved durability and reliability (supports fatigue planning)

- Reduced trial-and-error fixes late in development

- More confident sign-off with traceable documentation

Common scenarios where dynamic analysis is essential

Consider dynamic analysis whenever the product sees time-varying excitation, including:

Vibration & cycling

- Motors, engines, rotating equipment

- Fans, pumps, compressors

- Operational cycling at known frequencies

Shock & transport

- Shipping / handling / drop events

- Vehicle mounting loads

- Sudden acceleration / impact

Typical applications include brackets, frames, enclosures, electronic assemblies, precision instruments, aerospace and automotive components, and industrial machinery.

Dynamic analysis as a strategic risk-reduction tool

For decision makers, dynamic analysis is less about mathematical detail and more about controlling uncertainty. It reveals how a product responds under realistic conditions and helps teams prioritize design changes where they matter most.

- Reduces late-stage surprises

- Shortens validation cycles

- Improves robustness without unnecessary overdesign

How dynamic fits into a complete validation strategy

Dynamic analysis is strongest when paired with static and fatigue assessments. Together:

- Static analysis: Can the product carry its loads?

- Dynamic analysis: How does it respond to motion and vibration?

- Fatigue analysis: How long will it last under cyclic loading?

Skipping dynamic analysis often means discovering issues only after prototypes, testing, or customer feedback— when fixes are most expensive.

Which dynamic method is used

Dynamic analysis is not one tool—it’s a family of methods chosen based on the load type and objectives:

Common methods

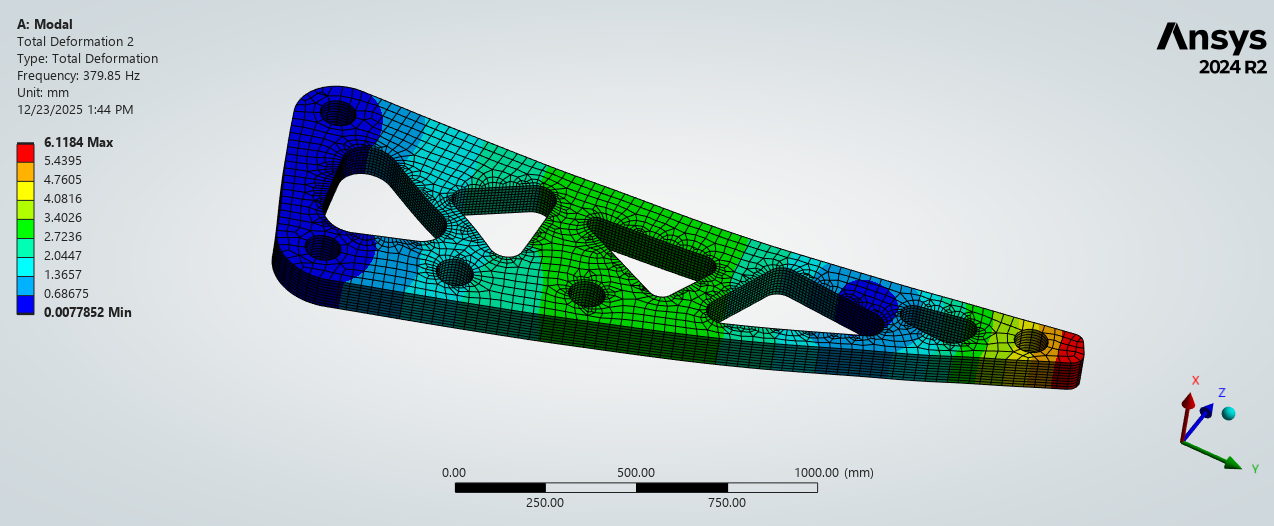

- Modal (natural frequencies + mode shapes)

- Harmonic response (steady sinusoidal excitation)

- Transient (time-domain events, shocks)

- Random vibration (PSD-based environments)

- Response spectrum (seismic / qualification)

Typical outputs

- Resonant frequencies and risk bands

- Peak deformation and stress amplification

- Hotspot locations tied to design features

- Design recommendations to shift modes / reduce response

If vibration or time-varying loads exist, dynamic analysis should not be optional.

Tetra Elements helps teams integrate dynamic analysis early to reduce risk and accelerate confident design decisions. We’re ready to sign an NDA.

Note: The right method (modal, harmonic, transient, random, response-spectrum) depends on the excitation type, constraints, damping assumptions, and design objectives.